Your blog post

Blog post description.

11/27/202510 min read

Climbing Yourself: Anxiety, Queer Identity, and “Mindspace” in Celeste (2018)

When people talk about hard platformers, they usually focus on speedruns and precision jumps. Celeste (Matt Makes Games, 2018) looks like that kind of game at first, but as you keep playing it becomes clear that the real challenge is not just the mountain. It is Madeline’s anxiety, depression, and complicated sense of self that you climb through, one tiny room at a time. Following Bizzocchi and Tanenbaum’s idea of close reading as a way to unpack how games create meaning through narrative, mechanics, and emotion (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011, 2012), I treat Celeste as a playable text rather than just a “difficult game.”

My thesis is that in Celeste (2018), the mountain storyworld as mindspace, the game’s demanding but adjustable platforming mechanics, and Madeline’s fragmented queer and possibly trans self all work together to transform anxiety and self-doubt into a hopeful model of mental-health resilience. I organize my argument around three high level concepts: (1) storyworld as mindspace where mental states are mapped onto spaces, (2) embodied difficulty and self-efficacy where repeated failure becomes a learning loop, and (3) fragmented queer/trans self-representation where Madeline’s double personifies internal conflict instead of a simple villain. Each concept comes from or connects to game-studies scholarship, especially work on mental health in indie games (Wischert-Zielke, 2025), serious games about depression (Hoffman, 2019), demographic and queer representation (Shaw, 2009; Williams et al., 2009), and a recent article directly reading Celeste through trans representation (McPhail, 2025).

Figure 1. Madeline at the base of Celeste Mountain, introducing the climb as a personal and psychological challenge (Celeste, 2018).

1. Storyworld as mindspace: climbing through anxiety

Bizzocchi and Tanenbaum argue that close reading needs to look at “storyworld,” not just plot, because the spaces of a game quietly organize how we feel and what we notice (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011, 2012). In Celeste, the mountain is not a neutral backdrop. It behaves like a mindspace, a physical map of Madeline’s internal state.

Moritz Wischert-Zielke (2025) uses the term “mindspacing” to describe how indie games about mental health turn thoughts and emotions into explorable environments. In that sense, almost every area of Celeste is a different mental zone. An early dream sequence where Madeline’s reflection steps out of a mirror and chases her is not just spooky; the environment starts glitching, platforms fall apart under her feet, and the level layout tightens into narrow corridors. The world literally closes in, which mirrors how a panic episode can feel. Later, in a temple full of long corridors, one-way doors, and confusing keys, the level structure mimics getting lost in your own head. You know there must be a way forward, but each path keeps looping back, echoing anxious rumination.

igure 2. The mirror sequence turns anxiety and intrusive thoughts into a hostile, glitchy space inside the mountain mindscape (Celeste, 2018).

Wischert-Zielke’s analysis of indie mental-health games points out that these titles often alternate between suffocating spaces and calmer “breathing rooms” where the player can pause and reframe what is happening (Wischert-Zielke, 2025). Celeste does the same thing. After an intense section, the game often gives you a quiet campfire, a cable-car ride, or a simple walking scene where Madeline talks with another character. Instead of traditional cut-scenes, these are almost like safe zones where the mindspace opens up: the background shifts from cramped caves to wide skies, and the music calms down. These places do not remove her anxiety, but they show her learning coping strategies, such as the breathing exercise on the cable car.

If we zoom out to larger industry patterns, Celeste’s intimate mountain stands out against what Williams et al. (2009) call the “virtual census.” Their large content analysis of games shows how mainstream titles tend to recycle similar fantasies and demographic patterns, often sidelining complex psychology in favor of power fantasies. Celeste goes the other way. The mountain is small, personal, and messy. Its ruins, ghostly hotel, and distorted dreamscapes build a storyworld that insists mental health is part of everyday life, not a rare “crazy villain” case. The fact that this whole adventure fits into a single mountain reinforces the idea that Madeline is not saving the world. She is just trying to get through her own mind.

By reading the mountain as mindspace, we can see that Celeste already argues something about mental health before we even think about difficulty settings or identity. Anxiety is not treated as an invisible, private issue that only appears in dialogue. It is baked into slopes, platforms, and hazards. That sets up the next layer of the argument, where the game invites players to physically rehearse how to live with that anxiety through its demanding platforming loops.

2. Embodied difficulty, assist mode, and learning to trust yourself

From a distance, Celeste looks like an unforgiving platformer where players die hundreds or even thousands of times. That sounds like the kind of difficulty that usually leads to elitist “git gud” attitudes. However, the actual design of failure in Celeste feels very different. This is where the second high level concept, embodied difficulty and self-efficacy, becomes important.

Kelly Hoffman’s study of two depression-themed art games argues that repeated trial-and-error gameplay can give players “social and cognitive affordances” such as empathy, self-evaluation, and a sense of community (Hoffman, 2019). In her sample, players reported that the games helped them think differently about depression, partly because failure loops forced reflection rather than simple frustration. Celeste uses a similar structure. Each screen presents a small puzzle that looks impossible at first: spikes everywhere, just a few safe blocks, and very tight timing windows. You die, restart almost instantly, adjust your timing, and try again.

This fast death-restart cycle turns the controller into a kind of training tool. You practice not only mechanical precision, but also a calmer mindset. Instead of punishing you with long reloads or lost progress, the game treats death as information. Over time, your body learns that messing up is normal and that you can adjust and keep moving. If we connect this to Hoffman’s argument, the loop encourages a kind of self-efficacy: you feel that your actions still matter, even when you fail repeatedly (Hoffman, 2019). The game’s little messages after each chapter, such as the non-judgmental death counter, reinforce this mindset. They acknowledge that you died many times but frame it as persistence rather than shame.

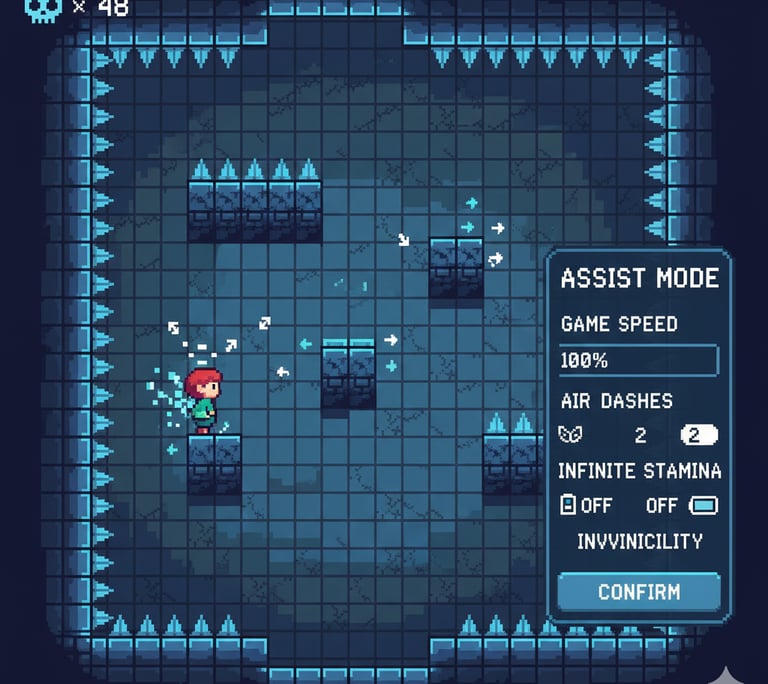

Figure 3. Repeated deaths and the optional Assist Mode show difficulty as practice and self-care rather than punishment (Celeste, 2018).

Wischert-Zielke (2025) notes that many indie games about mental health deliberately disrupt the idea that suffering proves authenticity. Instead, they highlight support, coping tools, and accommodations. Celeste’s Assist Mode does exactly that. At any time you can slow down the game, add extra dashes, or even become invincible. Importantly, the game does not hide this behind a “cheats” menu. It speaks directly to the player, saying that it is OK to adjust the experience and that doing so does not make the climb meaningless. This design lines up with contemporary mental-health thinking, where using medication, accessibility settings, or therapy is not a moral failure but an active strategy.

If we bring in Bizzocchi and Tanenbaum’s narrative framework, which emphasizes how mechanics and emotion interlock across a game’s design parameters (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2012), Celeste’s difficulty suddenly looks like a narrative device. The constant micro-failures and micro-successes map onto Madeline’s inner monologue. When she tells herself she cannot do this, the player has already proven the opposite through practice. The game quietly trains players to answer that voice with “actually, I learned this room; I can probably learn the next one.” That bodily knowledge matters when the story brings Madeline to her lowest emotional point and the player has to decide whether to keep climbing.

So in this middle section of the essay, difficulty is not just a gameplay feature. It becomes a metaphorical system that models anxiety not as something you beat once, but as something you negotiate through repeated effort, adjustments, and sometimes asking for help via Assist Mode.

3. Fragmented self and queer or trans representation

The third high level concept is fragmented queer or trans self-representation. In Celeste, Madeline’s darker double, often called “Badeline” by fans, is more than a regular antagonist. She is literally Madeline’s reflection, pulled out of a mirror and given a voice that constantly tells Madeline she will fail. This character dynamic connects with long-running conversations in game studies about queer representation and industry structures.

Adrienne Shaw’s article “Putting the Gay in Games” points out that LGBTQ content in mainstream games has often been limited, conditional, or pushed to the margins, and that industry assumptions about “the audience” shape what kinds of queer stories get told (Shaw, 2009). Williams et al.’s “virtual census” backs this up on a demographic level by showing that the majority of game characters are straight, cis, male, and white (Williams et al., 2009). Against this backdrop, Celeste stands out because its central emotional arc focuses on a young woman with anxiety who later turns out to be canonically trans, supported by a community of players rather than by marketing slogans.

Kyle McPhail’s recent article “Reflecting on Celeste: Abstracting Trans Representation” reads Celeste as an example of what he calls “abstract trans representation” (McPhail, 2025). Instead of having Madeline explicitly state “I am trans” in dialogue, the game builds a more metaphorical story about fragmented identity, fear of change, and eventual self-integration. McPhail argues that this abstraction can be powerful because it lets trans players see their experiences reflected without turning the game into a simple “issue story,” while still remaining legible to other players who read it more generally as a story about mental health.

The moments where Madeline confronts and then learns to cooperate with her double match this idea closely. At first, she treats Badeline as a monster to escape. The game mechanically expresses this through chase sequences where the double multiplies and blocks your path. Later, after a major breakdown, Madeline decides to stop fighting her and asks what she is afraid of. The two characters literally climb together. After they merge, Madeline gains an extra air dash. The new movement ability is not just a reward for beating a boss. It is a mechanical symbol of integration: by accepting the part of herself she used to reject, she becomes more mobile, more capable, and more herself.

Figure 4. Madeline’s reconciliation and fusion with her double frame queer and possibly trans identity as integration rather than erasure (Celeste, 2018).

Seen through Shaw’s and Williams et al.’s work, this is an important shift (Shaw, 2009; Williams et al., 2009). Queer or trans characters in games have often been either invisible or trapped in tragic endings. Celeste does not erase Madeline’s anxiety or identity at the summit. Instead, it suggests that embracing those parts of herself is what lets her reach the top. McPhail (2025) notes that this can resonate strongly with trans players who recognize the fear, self-doubt, and relief that come with transition or coming out.

By making the fragmented self central to both the story and the mechanics, Celeste avoids turning transness or queerness into a side quest. The player literally cannot finish the game without playing as the merged Madeline who has accepted and incorporated her double. That means that identity and mental health are structurally necessary to the experience, not optional decoration.

Conclusion: The climb after the credits

Putting these three high level concepts together shows how tightly Celeste is designed around mental-health and identity themes. First, the mountain functions as a mindspace, following Wischert-Zielke’s idea of indie “mindspacing,” so that every windy ridge and glitchy corridor reflects something about Madeline’s emotional state (Wischert-Zielke, 2025). Second, the demanding but forgiving platforming, analyzed through work on depression-themed games and self-efficacy (Hoffman, 2019), teaches players that failure is information and that adjusting the rules through Assist Mode is an act of care, not cheating. Third, the relationship between Madeline and her double, read through queer and trans game-studies scholarship (McPhail, 2025; Shaw, 2009), turns fragmented identity into a source of new abilities rather than a flaw to be erased. All of this happens within an industry landscape that, as the “virtual census” shows, still struggles with inclusive representation (Williams et al., 2009).

Bizzocchi and Tanenbaum describe close reading as a way to move beyond simply “liking” a game toward understanding how its pieces work together (Bizzocchi & Tanenbaum, 2011, 2012). A close reading of Celeste reveals a carefully layered design where storyworld, mechanics, and character are all pulling in the same direction. The game never pretends that anxiety or transness can be cured by a single heroic act. Instead, it shows that living with these realities feels more like climbing a mountain that never truly goes away. You rest, you slip, you try again, and sometimes you change the rules to make the path possible.

In that sense, the most important thing about Celeste is not that Madeline reaches the summit. It is that the climb teaches both her and the player a new way to think about struggle. The mountain is still there after the credits, but so is the knowledge that you can keep climbing, even when the hardest part is inside your own head.

References

Bizzocchi, J., & Tanenbaum, T. J. (2011). Well read: Applying close reading techniques to gameplay experiences. In D. Davidson (Ed.), Well Played 3.0: Video games, value and meaning (pp. 262–290). ETC Press.

Bizzocchi, J., & Tanenbaum, T. J. (2012). Mass Effect 2: A case study in the design of game narrative. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 32(5), 393–404.

Hoffman, K. M. (2019). Social and cognitive affordances of two depression-themed games. Games and Culture, 14(7–8), 875–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017742307 (SAGE Journals)

Matt Makes Games. (2018). Celeste [Video game].

McPhail, K. (2025). Reflecting on Celeste: Abstracting trans representation. Games and Culture, 20(4), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231204148 (SAGE Journals)

Shaw, A. (2009). Putting the gay in games: Cultural production and GLBT content in video games. Games and Culture, 4(3), 228–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009339729 (SAGE Journals)

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., & Ivory, J. D. (2009). The virtual census: Representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105354 (SAGE Journals)

Wischert-Zielke, M. (2025). Mindspacing and play: Indie games in the context of mental health depiction. Game Studies, 25(3). https://gamestudies.org/2503/articles/wischertzielke (Game Studies)

AI Acknowledgement

I used AI (ChatGPT, GPT-5.1 Thinking by OpenAI) to help co-create this paper. I asked it to:

Suggest and refine high level concepts for analyzing Celeste and connect them with course readings.

Help locate relevant academic sources from the required game-studies journals (for example: “Find recent Game Studies or Games and Culture articles about mental health and Celeste”).

Draft and reorganize sections of the essay using prompts such as: “Write about 500 words on how Celeste’s difficulty and Assist Mode relate to self-efficacy and mental-health games, with in-text APA citations.”

After receiving AI-generated text and citation suggestions, I checked the sources through online databases, edited the language, adjusted the structure to fit the assignment instructions, and made sure the argument matched my own understanding of the game and course material. Any remaining mistakes in interpretation, wording, or citation are my responsibility.